|

|

Description

This species can be distinguished from the sympatric spotted-necked otter by its larger size (10 – 21kg, males larger than females), greater length (120 - 150 cm), paler color ventrally and lack of spotted markings on the throat, very long vibrissae, almost no webbing on toes (hind feet partially webbed), and generally a complete lack of claws on the toes.

The Cape clawless otter, one of three “clawless” otter species looks very similar to all other “river” otter species. The long body is set on short legs with the hind legs longer than the front causing them to lope when they run. Claws are almost completely absent but for short grooming claws occasionally seen on the third and fourth digits of the hind limbs, and all digits are unwebbed. Like the other clawless otters and sea otter they rely on their dexterous and sensitive hands to capture prey. The tail is long, stout, and tapered toward the tip. The sides of the face, neck, throat, belly and ear edges are white to cream colored. The dorsal portion of the coat is dark brown, greyish-brown or pale tan, dense, and lustrous. Guard hairs can reach 25mm; the underfur is lighter in color and much finer than the guard hairs. The whiskers are whilte. long and numerous. Like the other otters the Cape clawless depends on its coat, and not layers of fat for warmth. The Cape clawless otter possesses a pair of anal scent glands used for scent-marking.

Dentition is adapted for crushing crustaceans and skull bones of large fish.

CITES Identification Sheet

Afrikaans: Groototter

English: African clawless otter

French: Loutre à joues blanches

German: Weisswangen-Otter, Fingerotter

Kiswahili: fisi maji kubwa

Swahili: Fisi Madji

Tswana: leNyibi

Xhosa: inTini

Zulu: umThini

Habitat

This species occupies a range of habitats from rainforests to open plains and, at least historically was found in semi-arid country. Their only requirement is that they live near water and can be found occupying rivers, streams, reservoirs, lakes with clear water, swamps and streams, fish farms, canals and ditches, and also beaches, rocky shores, mangroves, and mudflats - wherever sufficient food is available. They will travel widely over unsuitable habitat in search of new feeding grounds. Populations of Cape clawless otters are known from coastal areas of South Africa where they are known to forage equally in the sea and coastal freshwater marshes.

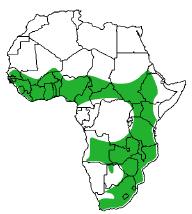

Distribution

The Cape clawless otter’s distribution, which is closely associated with water systems, extends from Senegal in the west, to Ethiopia in the northeast, and south to South Africa.

Conservation Status

Red List Category Near Threatened, Decreasing

Year Assessed 2014

Assessor Jacques, H.

Evaluators Hussain, S.A. (Otter Red List Authority)

CITES Appendix II

Current Concerns

At present, this species is not under severe pressure. The most important threats to the Cape clawless otter today are increasing human populations and the resulting changes to their habitats. These include pollution of water systems, increased siltation and agricultural run off and the introduction of the Louisiana red crayfish which has altered the prey base in some of their previous range. While the otter does prey on the crayfish, the seasonality of the crayfish and heavy predation on them by other species appears to have impacted the otters in some areas (Ogada 2005 and in prep.). Additionally, the otter is hunted for its pelt and medicinal purposes in some areas and killed in others as a perceived competitor for fish, particularly in areas where the rainbow trout has been introduced. The impact of persistent drought in parts of their former range and the seasonal disappearance of streams and rivers previously known to flow year around has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

Although legal protection is in place, it needs to be enforced on the ground. Greater awareness of the species, its needs, and its importance in indicating good human habitat is needed amongst the public and local authorities. Further research is needed on distribution, population dynamics, ecology, threats and cultural relevence, in order to devise useful management principles. As a precautionary measure, protected areas should be established with the support of local communities.

Current Research and Conservation Priorities (OSG Frostburg, MD 2004)

The following priorities were established for Africa during the last meeting of the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group:

- to expand the network of information sources on otter distribution data by establishing further cooperation with conservation and research institutions or projects being already active in Africa and targeting even at other species, with African universities and research agencies, with park and reserve staff, and with safari and tourist guides.

- to establish a network of qualified trainers and advisors (from Africa and from abroad) having practical experience with field work on otters in Africa, who are willing and able to train and to advise newcomers for survey and research projects.

- to identify priority areas where research on the distribution of and/or on threats to otters should be carried out if financial and personnel resources are available.

to take action via international or national bodies to achieve that otters and their habitats will receive protection in more than the 29 out of 54 African countries where they currently afford full or partial (i.e. only in conservation areas) protection.

Leading Researchers

David Rowe-Rowe, Jan Nels, Michael Somers, Mordecai Ogada, L.H. Watson, A.J. Lang, C.H.G., Arden-Clarke, C. Carugati, D. van der Zee.

Key Publications

- Arden-Clarke, C. H. G. (1986). Population density, home range size and

spatial organization of the Cape clawless otter, Aonyx capensis, in a marine

habitat. J. of Zoo., London 209:201-211.

- Baranga, J. (1995). The distribution and conservation status of otters

in Uganda. Habitat 11:29-32.

- Butler, J. R. A. (1994). Cape clawless otter conservation and a trout

river in Zimbabwe: a case study. Oryx 28:276-282.

- Butler, J. R. A. & Du Toit, J. T. (1994). Diet and conservation

status of clawless otters in eastern Zimbabwe. South African J. of Wild.

Research 24:41-47.

- Carugati, C., Rowe-Rowe, D. T., Perrin,M. R. & Reuther, C.. (1993). Habitat use by two species of otters in the Natal Drakensberg, South Africa. In: Proceedings VI International Otter Colloquium, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 1993. C. Reuther & D. Rowe-Rowe editors. Aktion Fischotterschutz, Hankensbüttel, Germany, Habitat 11:29-32.

- Carugati, C., Rowe-Rowe, D. T. & Perrin, M. R. (1995). Habitat use by Aonyx capensis and Lutra maculicollis in the Natal Drakensberg, South Africa: Preliminary results. Hystrix 7(1/2):239-242.

- Donnelly, B. G. & Grobler, J. H. (1976). Notes on food and anvil using behaviour by the Cape clawless otter, Aonyx capensis, in the Rhodes Matopos National Park, Rhodesia. Arnoldia Rhodesia 7:1-8.

- Koepfli, K. P. & Wayne, R. K. (1998). Phlyogenetic relationships of otters (Carnivora: Mustelidae) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences. J. of Zool, London 246:401-416.

- Kruuk, H. & Goudswaard, P. C. (1990) Effects of changes in fish populations in Lake victoria on the food of otters (Lutra maculicollis Schinz and Aonyx capensis Lichtenstein). African J. of Ecology 28:322-329.

- Larivière, S. (2001). Aonyx capensis. Mammalian Species Sheets, No. 671, 6pg. American Society of Mammalogists.

- Ligthart, M. F., Nel, J. A. J. & Avenant, N. L. (1994). Diet of Cape clawless otters in part of the Breede River system. South African J. of Wildl. Research 24:38-39.

- Mason, C. F. & Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1992). Organochlorine pesticide residues and PCBs in otter scats from Natal. South African J. of Wildl. Research 22(1):29-31.

- Maxwell, G. (1963). Ring of bright water. Longmans Green, London.

- Nel, J.A.J. & Somers, M. (1998). The status of otters in Africa: An assessment. Proceedings of the VII International Otter Symposium, 13-19 March 1998. Trebon, Czech Republic.

- Ogada, M. O. (2005). Effects of the Louisiana crayfish invasion on the food and territorial ecology of the African clawless otter in the Ewaso Ng'iro ecosystem, Kenya'-PhD thesis, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Ogada, M.O., Aloo, P. A., & Muruthi, P. M., (2006) Effects of the Louisiana crayfish invasion on the food and territorial ecology of the African clawless otter in the Ewaso Ng'iro ecosystem. Submitted to 'Biological Conservation' (In review)

- Perrin, M. R. & Carugati, C.. (2000). Habitat use by the Cape clawless otter and spotted-necked otter in the KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg, South Africa. South African J. of Wildl. Research 30(3):103-113.

- Perrin, M. R. & Carugati, C. (2000b). Food habits of coexisting Cape clawless otter and spotted-necked otter in the KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg, South Africa. South African J. of Wildl. Research 30(2):85-92.

- Purves, M. G., Kruuk, H. & Nel, J. A. J. (1994). Crabs Potamonautes perlatus in the diet of otter Aonyx capensis and water mongoose Atilax Paludinosus in a freshwater habitat in South Africa. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 59:332-341.

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1977a). Food ecology of otters in Natal, South Africa. Oikos 28:210-219.

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1977b). Prey capture and feeding behaviour of South African otters. The Lammergeyer 23:13-21.

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1977c). Variations in the predatory behaviour of the clawless otter. The Lammergeyer 23:22-27.

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1978). Biology of the two otter species in South Africa. Pp. 130-139 in Otters (N. Duplaix ed.): Proceedings of the first working meeting of the Otter Specialist Group. International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland.

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1985). Facts about otters. Wildlife Management – Technical Guides for Farmers, Natal Parks Board, Pietermaritzburg 10:1-2

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1986). African otters – is their existence threatened? International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 1:9-11.

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. (1992). Survey of South African otters in a fresh-water habitat, using sign. South African J. of Wildl. Research 22:49-55.

- Rowe-Rowe, D.T. (1995). The distribution and status of African otters. Proceedings of the VI International Otter Symposium, September 6-10, 1993, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Habitat No.11, Hankensbüttel, Germany.

- Rowe-Rowe, D. T. & Somers, M. J. (1998). Diet, foraging behaviour and coexistence of African otters and the water mongoose. Symposia of the Zool. Soc. of London 71:216-227.

- Smith, L. (1993). Otters and gillnet fishing in Lake Malawi National Park. International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 8:4-6.

- Somers, M. J.(2000). Foraging behaviour of Cape clawless otters Aonyx capensis in a marine habitat. J. of Zool, London 252:473-480.

- Somers, M. J. & M. G. Purves, (1996). Trophic overlap between three syntopic semi-aquatic carnivores: Cape clawless otter, spotted-necked otter and water mongoose. African J. of Ecology 34:158-166.

- Van der Zee, D. (1981). Prey of the Cape clawless otter Aonyx capensis in the Tsitsikama Coastal national Park, South Africa. J. of Zool., London 194:467-483.

- Van der Zee, D. (1982). Density of Cape clawless otters Aonyx capensis (Schinz 1821) in the Tsitsikama Coastal National Park. South African J. of Wildl. Research 12:8-13.

- Van Niekerk, C. H., Somers, M. J. & Nel, J. A. J. (1998). Fresh-water availability and distribution of Cape Clawless otter spraints and resting places along the south-west coast of South Africa. South African J. of Wildl. Research 28:68-72.

- Verwoerd, D. J. (1987). Observations on the food and status of the Cape clawless otter Aonyx capensis at Betty’s Bay, South Africa. South African J. of Zool. 22:33-39.

Useful Links

|